[ad_1]

The Facebook engineer was eager to know why his companion hadn’t responded to his messages. Perhaps there was a simple explanation – maybe she was sick or on vacation.

One day at 10:00 pm at the company’s headquarters in Menlo Park, he opened her Facebook profile on the company’s internal systems and began looking at her personal data. Her politics, her lifestyle, her interests – even her whereabouts in real time.

The engineer would be fired for his behavior along with 51 other employees who misused their access to company data, a privilege that was then available to everyone who worked at Facebook, regardless of their job function or seniority. The vast majority of 51 were exactly like him: men looking for information about women of interest.

In September 2015, after new Chief Security Officer Alex Stamos brought the issue to Mark Zuckerberg’s attention, the CEO ordered a system overhaul to restrict employee access to user data. It was a rare victory for Stamos, in which he convinced Zuckerberg that Facebook’s design was to blame, not individual behavior.

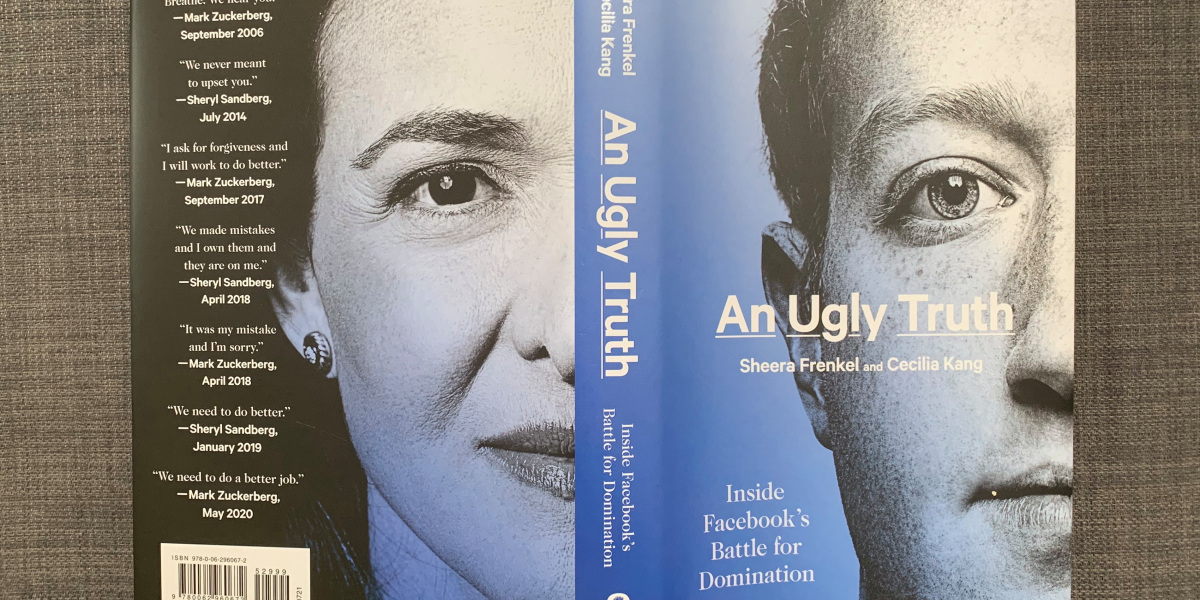

This is how it begins Ugly truth, a new book on Facebook by seasoned New York Times reporters Shira Frenkel and Cecilia Kang. With Frenkel’s expertise in cybersecurity, Kang’s expertise in technology and regulatory policy, and their extensive sources, the duo provides a compelling account of Facebook’s years spanning the 2016 and 2020 elections.

Stamos will be out of luck anymore. The problems stemming from Facebook’s business model only escalated in the following years, but when Stamos discovered more egregious problems, including Russian interference in the US elections, he was kicked out for forcing Zuckerberg and Sherrill Sandberg to admit an embarrassing truth. Since his departure, leadership has continued to refuse to tackle a range of deeply troubling issues, including the Cambridge Analytica scandal, the genocide in Myanmar, and rampant misinformation about the covid.

BEOWULF SHEEHAN

Frenkel and Kang argue that Facebook’s problems today are not the product of a company that has lost its way. Instead, they are part of his very vision, built on Zuckerberg’s narrow worldview, the culture of sloppy privacy he cultivated, and the overwhelming ambition he pursued with Sandberg.

When the company was still small, perhaps this lack of foresight and imagination could be justified. But since then, Zuckerberg and Sandberg’s decisions have shown growth and revenue to outperform everything else.

For example, in a chapter entitled “Company over the Country,” the authors describe how the leadership tried to hide the extent of Russian interference in platform elections from the US intelligence community, Congress, and the American public. They censored numerous attempts by Facebook’s security team to release details of what they found and carefully selected the data to downplay the severity and biased nature of the problem. When Stamos proposed restructuring the company to prevent a recurrence of the problem, other leaders dismissed the idea as “alarmist” and focused their resources on gaining control of public opinion and curbing regulators.

[ad_2]

Source link