[ad_1]

“This is a really exciting result,” says Edward Cuckett, an astronomer at Wayne State University who was not involved in the study. “Although we have seen the signature of X-ray echoes before, it has so far not been possible to separate the echoes that come from behind the black hole and fall into our field of view. This will improve the display of how things fall into black holes and how black holes warp space-time around them. “

The release of energy by black holes, sometimes in the form of X-rays, is an absurdly extreme process. And because supermassive black holes release so much energy, they are essentially powerhouses that allow galaxies to grow around them. “If you want to understand how galaxies form, you really need to understand these processes outside the black hole, which are capable of releasing enormous amounts of energy and power, these amazingly bright light sources that we are studying,” says Dan Wilkins. astrophysicist at Stanford University and lead author of the study.

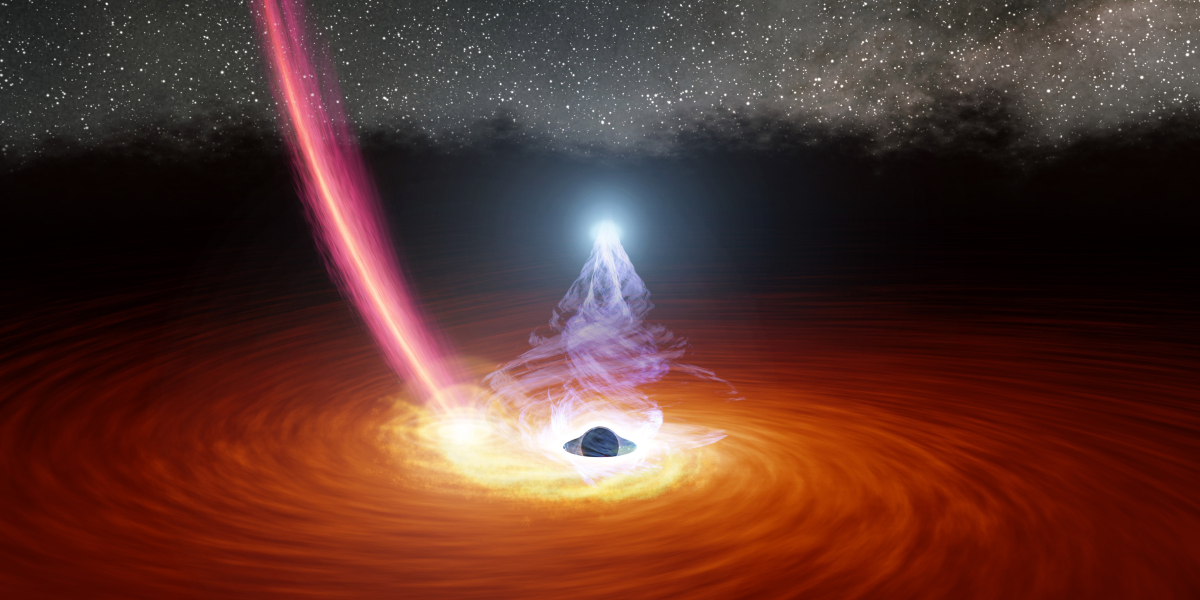

The study focuses on a supermassive black hole at the center of the galaxy, I Zwicky 1 (abbreviated as I Zw 1), about 100 million light-years from Earth. In supermassive black holes like I Zw 1, large amounts of gas fall towards the center (the event horizon, which is essentially a point of no return) and tend to turn into a disk. Above a black hole, the fusion of charged particles and magnetic field activity produces high-energy X-rays.

Some of these X-rays strike directly at us, and we can observe them normally through telescopes. But some of them also shine on the flat disk of gas and are reflected from it. The rotation of the I Zw 1 black hole slows down at a faster rate than is observed in most supermassive black holes, which makes the surrounding gas and dust easier to fall inward and feed the black hole from different directions. This, in turn, leads to an increase in X-rays, which is why Wilkins and his team were especially interested.

As Wilkins and his team watched this black hole, they noticed that the corona appeared to be “flaring up.” These flares, caused by pulses of X-rays bouncing off the massive disk of gas, emanated from the shadow of the black hole – a place that is usually hidden from view. But because the black hole bends the space around it, the X-ray reflections are also curved around it, which means we can detect them.

The signals were detected by two different space telescopes optimized for X-ray detection in space: NuSTAR, operated by NASA, and XMM-Newton, operated by the European Space Agency.

Most significant of the new discoveries is that they support Albert Einstein’s 1963 prediction in his general theory of relativity – the way light should bend around giant objects such as supermassive black holes.

“This is the first time we actually see a direct signature of light bending completely behind a black hole in the direction of our view. because about how a black hole distorts the space around it, ”says Wilkins.

“While this observation does not change our overall picture of black hole accretion, it is good evidence that general relativity plays a role in these systems,” said Erin Kara, an astrophysicist at MIT who was not involved in the study.

Despite the name, supermassive black holes are so far away that they actually look just like individual points of light, even with the most modern instruments. It will not be possible to photograph them all the way scientists used the Event Horizon telescope to capture the shadow of a supermassive black hole in galaxy M87.

So while it’s still early days, Wilkins and his team hope that detecting and studying more of these X-ray rotational echoes can help us create partial or even complete images of distant supermassive black holes. In turn, this could help them uncover some of the big mysteries of how supermassive black holes grow, support entire galaxies, and create an environment in which the laws of physics are pushed to their limits.

[ad_2]

Source link