[ad_1]

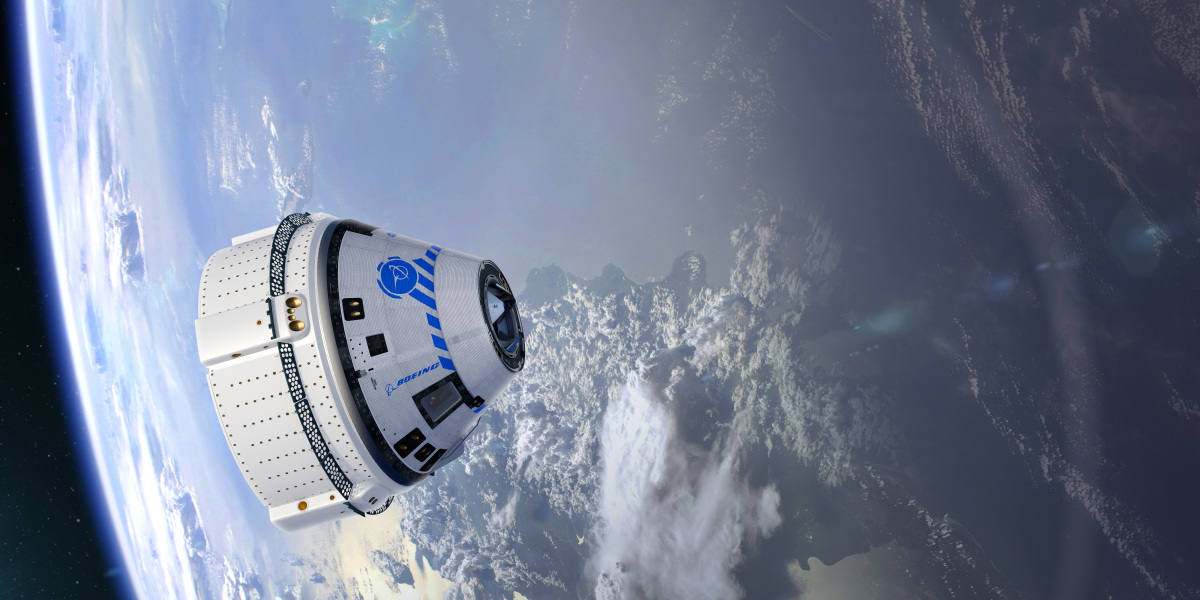

Now Boeing is about to repeat this mission in a big way. Orbital Flight Test 2, or OFT-2, will send the Starliner back to the ISS on August 3. The company cannot afford to fail again.

“There’s a lot of trust at stake,” says Greg Autry, a space policy expert at Arizona State University. “There is nothing more noticeable than the space systems that people fly on.”

The day of July 30 was a vivid reminder of this visibility. After the new Russian 23-ton multipurpose module “Nauka” docked with the ISS, it unexpectedly and without a command began to start the engines, displacing the ISS from its correct and normal position in orbit. NASA and Russia fixed the problem and stabilized the situation in less than an hour, but we still don’t know what happened, and it’s anxious to think what might have happened if conditions were worse. The incident is still under investigation and prompted NASA to postpone the Starliner launch from July 31 to August 3.

This is exactly how close to disaster Boeing wants to avoid for OFT-2 and any future missions with people on board.

How Starliner got here

The end of the space shuttle program in 2011 gave NASA an opportunity to rethink its approach. Rather than creating a new spacecraft designed for low-Earth orbit missions, the agency decided to open up opportunities for the private sector through a new commercial crew program. He has contracts with Boeing and SpaceX to build his own crewed vehicles, the Starliner and Crew Dragon, respectively. NASA will buy flights on these machines and focus its efforts on creating new technologies for flights to the Moon, Mars and other places.

Both companies faced development delays, and for nine years the only way for NASA to go into space was to donate millions of dollars to Russia for tickets for the Soyuz spacecraft. SpaceX finally sent astronauts into space in May 2020 (two more crewed missions have since followed), but Boeing is still lagging behind. His flight in December 2019 was to prove that all of his systems were working and that he was capable of docking with the ISS and returning safely to Earth. But a glitch with its internal clock caused a critical burn to be triggered prematurely, making it impossible to dock with the ISS.

Subsequent investigation revealed that the second glitch caused Starliner to fire its engines at the wrong time on its descent to Earth, which could have destroyed the spacecraft. This glitch was fixed just hours before the Starliner was due to return home. Software problems are not unexpected in spacecraft development, but they are something that Boeing could have addressed ahead of time if it had better quality control or oversight from NASA.

Boeing had 21 months to fix these problems. NASA has never required a Starliner to be re-flight tested; Boeing decided to redo it and pay the $ 410 million bill on its own.

“I am completely confident that the test will pass perfectly,” says Autry. “These problems are related to software systems and should be easy to fix.”

What’s at stake

If something goes wrong, the consequences will depend on what those things are. If the spacecraft has yet another set of software problems, it may have to pay a hell of a lot, and it’s very hard to see how Boeing’s relationship with NASA can be repaired. A catastrophic failure for other reasons would also be bad, but space is unstable, and even tiny problems that are difficult to foresee and control can lead to explosive results. This might be more excusable.

If the new test is unsuccessful, NASA will still work with Boeing, but a re-flight “could be in a couple of years,” says Roger Handberg, a space policy expert at the University of Central Florida. “NASA is likely to return to SpaceX for additional flights, further disadvantaging Boeing.”

Boeing needs the OFT-2 to perform well for reasons beyond just fulfilling a contract with NASA. Neither SpaceX nor Boeing built their new vehicles for missions to the ISS – each of them had big ambitions. “There is a real demand [for access to space] from wealthy people, which has been demonstrated since the early 2000s, when some of them flew the Russian Soyuz, says Autry. “There is also a very strong business of piloting sovereign astronaut teams from many countries who are not ready to build their own spacecraft.”

SpaceX is going to be very tough competition. He has private missions – his own and through Axiom Space – already slated for the next few years. Others are bound to appear, especially with Axiom, Sierra Nevada and others planning to build private space stations for paying visitors.

Boeing’s biggest problem is cost. NASA pays the company $ 90 million for space to get astronauts to the ISS, compared to $ 55 million for SpaceX. “NASA can afford them because after the shuttle problems, the agency didn’t want to be dependent on a single flight system – if it breaks, everything stops,” says Handberg. But private citizens and other countries are more likely to opt for the cheaper and more experienced option.

Boeing definitely needs good PR these days. It is building the main launch vehicle for the $ 20 billion space launch system, which will be the most powerful rocket in the world. But high costs and massive delays have turned it into a lightning rod for criticism. Meanwhile, alternatives such as SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy and Super Heavy, Blue Origin’s New Glenn, and ULA’s Vulcan Centaur have emerged or will debut in the next few years. In 2019, NASA’s inspector general examined a possible $ 661 million Boeing contract fraud. And the company is one of the protagonists at the center of a criminal investigation related to a previous application for a contract to land on the moon.

If ever Boeing wanted to remind people of what it can do and what it can do for the US space program, it’s next week.

“Another setback would have left Boeing so far behind SpaceX that they might have to think about major changes in their approach,” says Handberg. “For Boeing, this in show.”

[ad_2]

Source link